Countering the legacy of enslavement with hope and justice

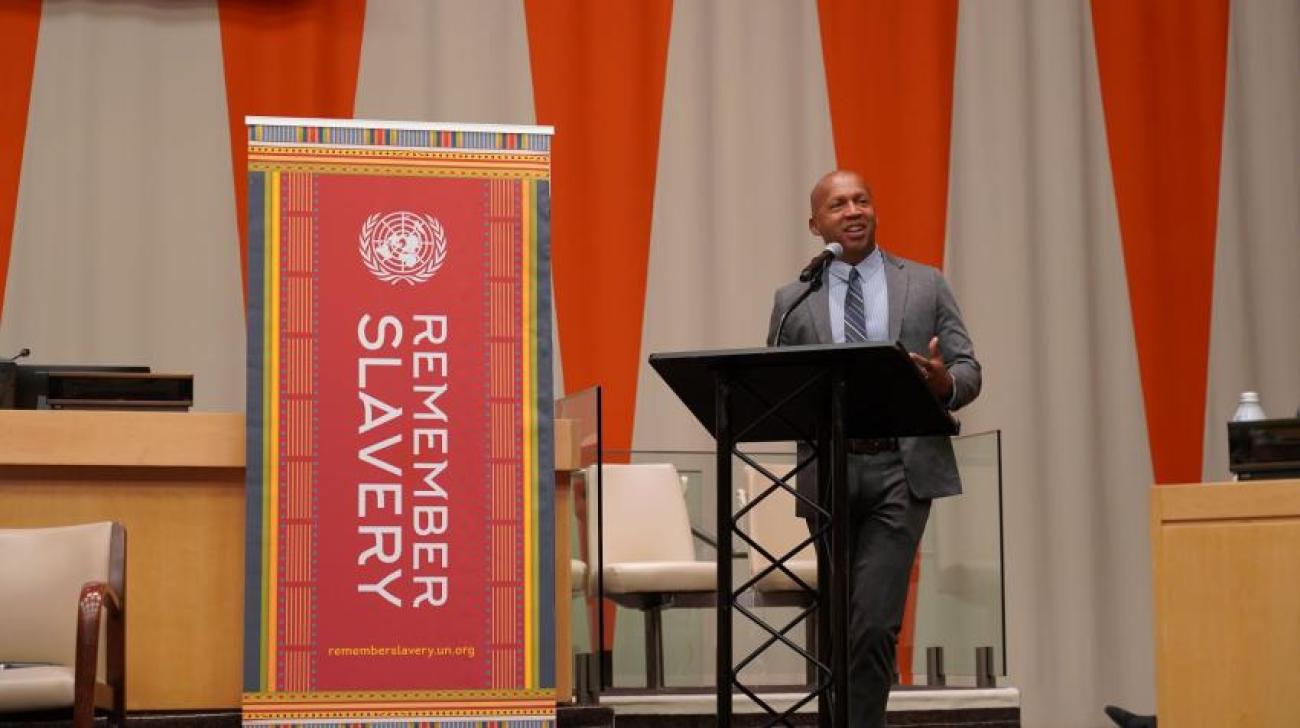

This UN Chronicle article was adapted from an interview conducted with the author by UN News on 2 April 2023.

The transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans was a global phenomenon. Beyond its obvious and profound impact on the peoples and countries of Africa, the trade in enslaved Africans also affected the nations of Europe. It created the American States—those of North, South and Central America—and had repercussions for Asia, as well.

As the world’s preeminent international organization, the United Nations is the only institution that can connect the multiple players and partners implicated in the global tragedy of the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans. It is thus appropriate and important that an institution like the United Nations take up the legacy issues surrounding the trade in enslaved Africans and centralize the importance of the story.

I’m a product of the 1954 United States Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education, in which the Court found that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, but I started my education in a “coloured school”, because Black children weren't permitted to attend the public schools where I lived.

Lawyers disrupted that reality. They came to my community with the power to enforce the rule of law, even though the majority of the people living there would not have voted to let kids like me into the schools. I was therefore drawn to what lawyers could do to protect disfavoured, marginalized, excluded people, and I went to law school with that objective in mind.

When I finished law school in the 1980s, people in our jails and prisons struck me as the most vulnerable part of our population. The number of people imprisoned in the United States increased from 300,000 in 1973 to 2.2 million in 2009. There were so many people facing execution, including children condemned to die in prison, that I decided to focus on that part of the problem. We continue to do that work.

"In culture, in museums—the realm of public history—I found a powerful opportunity to engage people."

But about 12 years ago, I began to fear that we might not be able to fulfil the promise of the landmark Supreme Court ruling that had created opportunities for me. I sensed a retreat from the commitment to apply the rule of law on behalf of disfavoured people. And that's when I looked to the humanities.

I started to believe that we had to engage in narrative work to begin getting people to understand the context of many of the issues facing Black people in the United States. In culture, in museums—the realm of public history—I found a powerful opportunity to engage people. We started developing scholarship and content on the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans, enslavement in America, lynching and segregation, but we also created cultural spaces that would invite people in.

I believe that this kind of invitation to learn and understand is desperately needed if we hope to achieve the level of consciousness around the world that is required to address the legacy of enslavement and the discrimination, bigotry and violence we still see today.

The Legacy Museum

In 2018, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) opened the Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration in Montgomery, Alabama, as a narrative museum. The Museum guides its visitors on a journey, one that begins with the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans. The first thing you'll see in the Legacy Museum is a gigantic wall that represents the Atlantic Ocean.

I grew up on the Atlantic coast in the United States, but it was only when I travelled to Africa and stood on the other side of the ocean that I began to realize the significance of that body of water when it comes to the African diaspora. In the Museum, we explore that history with animation that documents all the ships that transported 12 million Africans across the Atlantic. We dig deep into the location of the ports and the spaces in which people were abducted and held. In one animated video, Oscar-winning actor Lupita Nyong'o narrates the story of the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans.

The Legacy Museum also features a lot of art. One exhibit consists of 300 sculptures by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo that dramatize the humanity of the people who were enslaved. Often when we discuss enslavement, we make it seem so distant, so concrete, that we forget we're talking about people. The Legacy Museum emphasizes the impact of enslavement on its human victims.

The Museum journey leads visitors to a room with more sculptures and images to help people understand the legacy of the harm, the brutality. From there, the Museum sets out the history. It delves into the domestic trade in enslaved Africans in the United States, where a million people were trafficked to the American South.

Next, we examine the economic components of enslavement, which had global implications that we still haven't fully reckoned with. From there we talk about Reconstruction in America and later, lynching, which I see as a direct consequence of this era of enslavement. We discuss the codified racial segregation and racial hierarchy that existed in the United States. Across the globe, the false idea persists that somehow Black people aren't as good as white people. This fallacy hasn't been addressed with the kind of determination and intent that we feel is necessary.

Contemporary issues in context: The killing of George Floyd

One of the great evils of American enslavement was that it created a narrative in which Black people are presumptively dangerous, presumptively guilty, that they are not the same as white people. And that narrative gave rise to an ideology of white supremacy. The North may have won the American Civil War, but the narrative was won by the South because we held on to those ideas of racial hierarchy long after the war ended. This resulted in a century of violent terrorism directed towards Americans of African descent. Black people were pulled from their homes and drowned, tortured and lynched; and our legal system did not respond.

As a result of this legal inaction, we became acculturated to tolerating extreme violence against African Americans who, in most instances, had done nothing wrong. We codified that racial hierarchy, and the presumption of dangerousness and guilt continued even after the passage of civil rights laws in the 1960s. We're still contending with those false, negative presumptions today.

The great burden in America—the reason why so many people took to the streets when George Floyd was killed by police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in 2020—is that you could be a doctor or a lawyer or a teacher, you could be kind and loving, but if you're black or brown, there are places in this country where you have to navigate presumptions of dangerousness and guilt. I'm getting older, and I can tell you that having to constantly navigate these presumptions is exhausting.

This must change. Many of us are calling for a new era of truth and justice in America. Truth and reconciliation, truth and restoration, truth and reparation around this narrative have never been adequately addressed. The police violence that we see today, the bigotry, the presumption that someone in a coffee shop is doing something wrong when they're just drinking their coffee—all of these wrongs are manifestations of a narrative struggle in which we must engage.

This is where culture and art and museums and every institution in the world can play a role. It's when we name and acknowledge the history, and we are intentional about addressing it, that we begin to change the dynamic and create a new era. I am impressed by the Apartheid Museum in South Africa and the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin, which represent a kind of reckoning with difficult histories that we haven't fully undertaken in America, or in many places where the legacy of enslavement is felt.

The role of the United Nations

One of the many tragedies of the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans is that people were disconnected from their communities, their tribes, their families and their homes. The rupture was violent, and reconnecting these fundamental pieces of the social structure is thus difficult. If I were to take a DNA test to map my heritage, it would indicate connections to about 16 West African countries.

There must be a more global response to how we recover, how we repair the damage, how we heal from the multiple ways in which wealth and power were built in certain places, and how poverty and destruction and violence were experienced in other places. I believe that responding to the disparity between those who profited and those who were beaten and tormented is the obligation of any just society. It is therefore critically important that the United Nations take on a leading role in highlighting the need for reckoning, for repair, for conversation and dialogue around the multiple ways in which the legacy of enslavement continues to burden us today.

"I could never have imagined, even a decade ago, that we would be able to advance the process of justice as far as we have. And for me, the struggle for justice has always required hope."

Hope and justice

I'm extremely hopeful about the future. The fact that we now have a museum that attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors each year, and that we're now engaged in narrative work at a high level, gives me a great deal of hope. I could never have imagined, even a decade ago, that we would be able to advance the process of justice as far as we have. And for me, the struggle for justice has always required hope. In fact, I see hopelessness as the enemy of justice; injustice prevails where hopelessness persists. I look to my enslaved fore-parents for that hope because I'm the product of people who were, indeed, burdened and abused and humiliated by enslavement, but who also carried enough hope to find love, to live and create new generations. I am one of their descendants, and I carry the hope of my fore-parents just as I carry an awareness of the trauma and the harm.

I am very hopeful that we're now having conversations in places like the United Nations; that we're having conversations in academic spaces across the globe; that museums, which have long been silent, are now intentional in addressing these histories and realities with care and thought, centring the voices of people who were enslaved. This represents a remarkable step forward, and it gives me even more hope that we can someday arrive at a different reality.

The final point we make in the Legacy Museum is that its purpose is to create a world in which the children of our children are no longer burdened by the legacy of enslavement, no longer face presumptions of dangerousness and guilt. That is our ultimate aspiration, and I will carry it with me until we achieve those ends. I encourage everyone to embrace that same hope.

........................................

The UN Chronicle where this article was first published is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.