The Legacy of Slavery in the Caribbean and the Journey Towards Justice

From UN Chronicle, written by Ambassador A. Missouri Sherman-Peter, Permanent Observer of the Caribbean Community (CARICOM) to the United Nations.

It is now universally understood and accepted that the transatlantic trade in enchained, enslaved Africans was the greatest crime against humanity committed in what is now defined as the modern era. In terms of its scale and its social, psychological, spiritual and physical brutality, specifically inflicted upon Africans as a targeted ethnicity, this vastly profitable business, and the considerable subsequent suppression of the inhumanity and criminal nature of slavery, was ubiquitous and usurping of moral values.

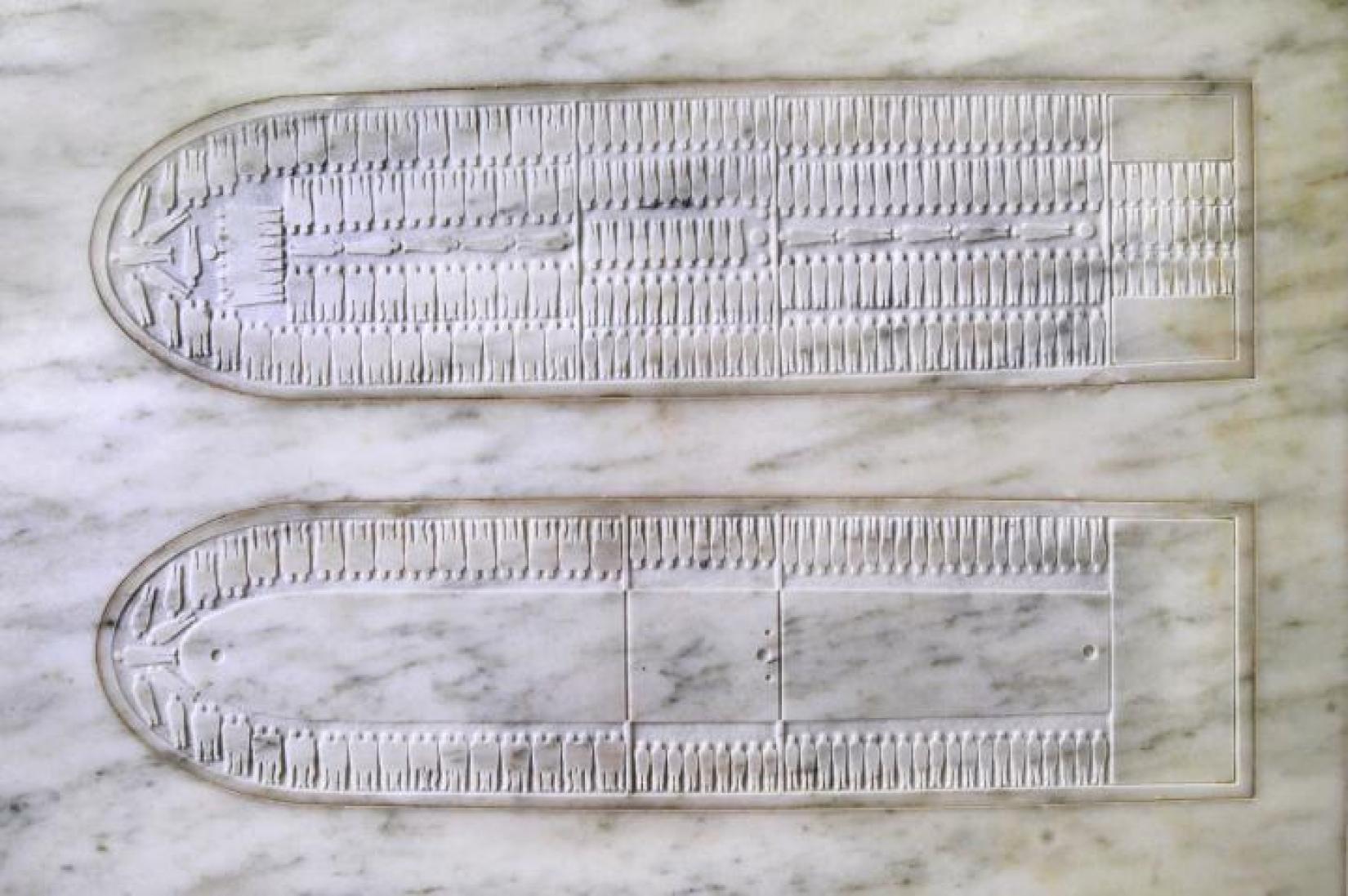

The demographics that the juggernaut economic enterprise of the slave trade and slavery represented are today well known, in large measure thanks to nearly three decades of dedicated scientific and historical research, driven significantly by the United Nations Educational Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and by recent initiatives, including the United Nations Outreach Programme on the Transatlantic Slave Trade and Slavery. Some 12 to 20 million Africans were enslaved in the western hemisphere after an Atlantic voyage of 6 to 10 weeks. This voyage, now known as the “Middle Passage”, consumed some 20 per cent of its “human cargo”. Disease and death were common outcomes in this human tragedy.

The Caribbean was at the core of the crime against humanity induced by the transatlantic slave trade and slavery. Some 40 per cent of enslaved Africans were shipped to the Caribbean Islands, which, in the seventeenth century, surpassed Portuguese Brazil as the principal market for enslaved labour. The sugar plantations of the region, owned and operated primarily by English, French, Dutch, Spanish and Danish colonists, consumed black life as quickly as it was imported.

Capitalism and black slavery were intertwined. The Atlantic economy, in every aspect, was effectively sustained by African enslavement.

Critically, the Caribbean was where chattel slavery took its most extreme judicial form in the instrument known as the Slave Code, which was first instituted by the English in Barbados. Passed in 1661, this comprehensive law defined Africans as “heathens” and “brutes” not fit to be governed by the same laws as Christians. The legislators proceeded to define Africans as non-human—a form of property to be owned by purchasers and their heirs forever. The Slave Code went viral across the Caribbean, and ultimately became the model applied to slavery in the North American English colonies that would become the United States.

Barbados in the Caribbean became the first large-scale colony populated by a black majority, and South Carolina in the United States assumed the same status. In this way, black enslavement became the primary institution for social and economic governance in the hemisphere. It was the basis of wealth creation in both production and commerce. In most societies, slavery investors emerged as the political and economic elite. Capitalism and black slavery were intertwined. The Atlantic economy, in every aspect, was effectively sustained by African enslavement.

The legacy of the social and economic institution of slavery is to be found everywhere within these societies and is particularly dominant in the Caribbean. While colonialism has been in retreat since the nationalist reforms of the mid-20th century, it persists as a political feature of the region. Europe remains a colonial power over some 15 per cent of the region’s population, and the relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico is generally understood as colonialist.

Most Caribbean societies possess large or majority populations of African descendants. The many legacies of over 300 years of slavery weighing on popular culture and consciousness persist as ferociously debilitating factors. The scourge of racism based on white supremacy, for example, remains virulent in the region. Institutional racism continues to be a critical force explaining the persistence of white economic dominance. The practice of political democracy has been effective in driving a culture of economic equity, but there remains a considerable amount of work to be done in creating a level playing field for all.

Fifty years ago, in 1972, George Beckford, an Economics Professor at the University of the West Indies, published a seminal monograph entitled Persistent Poverty, in which he explained the impoverishment of the black majority in the Caribbean in terms of the institutional mechanism of the colonial economy and society. The relevance of Beckford’s thesis remains striking today, and conversations about the legitimacy of democracy still reverberate around his research.

Then there are concerns regarding the standard markers of economic underdevelopment, such as widespread illiteracy, endemic hunger, systemic child abuse, inadequate public health facilities, primitive communications infrastructure, widespread slum dwelling, and chronically low enrolment and student performance at all levels of the education system. The Caribbean has the lowest youth enrolment in higher education in the hemisphere, an indication of the hostility to popular education under colonialism that is resilient in recent public policy. Extreme social and racial inequality is a legacy of slavery in the region that continues to haunt and hinder the development efforts of regional and global institutions.

Before the arrival and devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Caribbean region was buckling under the strain of proliferating, chronic non-communicable diseases.

Colonialism has persisted for over a century after the ending of formal slavery, leaving black communities to deal with economic despair and the emerging political class to clean up the inherited colonial disarray. Black slavery was a modern form of racial plunder, and the obvious consequences of this economic extraction are seen in structural underdevelopment. The Caribbean is home to some of the most economically and socially exploited people of modernity.

Before the arrival and devastation of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Caribbean region was buckling under the strain of proliferating, chronic non-communicable diseases. The rate of increase in the occurrence of type 2 diabetes and hypertension within the adult population, mostly people of African descent, was galloping. This other pandemic is discussed in terms of the racist culture of colonialism, in which the black population is generally considered addicted to foods containing high levels of sugar and salt.

It is frequently observed that 60 per cent of the black population in the region over the age of 60 years is afflicted with type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Jamaica and Barbados, the two historic giants of plantation sugar production and slavery, now struggle to avoid amputations that are often necessitated by medical complications resulting from the uncontrolled management of these diseases.

Resistance to the oppression of slavery and ethnic colonialism has made the Caribbean a principal site of freedom politics and democratic desire. Revolts on slave ships cascaded into rebellions on plantations and in towns. Popular and grass-roots activism have created a legacy of opposition to racism and ethnic dominance. The Caribbean is home to the Haitian Revolution, which produced the world’s first black freedom state and the subsequent proliferation of constitutional democracies.

The Black Lives Matter Movement is therefore equally rooted in Caribbean political culture, which served to nurture the indigenous United States upsurge. Together they laid the foundation for a twenty-first century global contribution to political reform with a democratic sensibility.

Presenting evidence of past wrongs now facilitates the call for a new global order that includes fairness in access and equality in participation.

The post-colonial, post-modern world will never be the same as a result of this legacy of resistance and the symbolism of racial justice—key elements of humanity rising to its finest and highest potential. Eliminating the toxic contaminant of hierarchical ethnic racism from all societies, and allowing them to embrace a horizontal perspective on ethnic and cultural diversity and ways of living, will enable the twenty-first century to be better than any prior period in modernity.

It is for this and related reasons that the Caribbean has emerged as an epicenter of the global reparatory justice movement. Its campaign for reparations for the crimes of slavery and colonialism has served as a template for the Global South in seeking a level playing field for development within the international economic order. In addition, it serves as a model for new forms of equity, including in climate and public health justice. Presenting evidence of past wrongs now facilitates the call for a new global order that includes fairness in access and equality in participation.

The Caribbean contribution, therefore, will help make the world a safer place for citizens who insist that it is a human right to live free from fear of violence, ethnic targeting and racial discrimination. Current forms of slavery and extreme social oppression are now identified more clearly and treated with similar public and policy opposition as traditional forms. The Caribbean is well positioned to discharge this diplomatic obligation to the world in the aftermath of its own tortured history and long journey towards justice.

The region can and must be the incubator for a new global leadership that celebrates cultural plurality, multi-ethnic magnificence, and the domestication of equal human and civil rights for all as a matter of common sense and common living. In short, the Caribbean that began its modern history as a centre of crimes against humanity can turn this world on its head and be recast as the centre of a new consciousness that celebrates justice and freedom for all.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.