In 2009 the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed 29 August the International Day Against Nuclear Tests.

This date recalled the official closing of the Semipalatinsk nuclear weapons testing site in today’s Kazakhstan on 29 August 1991; that one site alone having seen 456 nuclear test explosions between 1949 and 1989.

Between 1954 and 1984 there was on average at least one nuclear weapons test somewhere in the world every week, most with a blast far exceeding the bombing of Hiroshima; nuclear weapons exploding in the air, on and under the ground and in the sea.

Radioactivity from these test explosions spread across the planet deep into the environment. It can still be traced and measured today, in elephant tusks, in the coral of the Great Barrier Reef and in the deepest ocean trenches.

Meanwhile nuclear weapons stockpiles have grown exponentially. By the early 1980s there were some 60,000 nuclear weapons, most far more powerful than the bombs used in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Public indignation grew. By the 1960s it was agreed in principle that ending explosive nuclear tests would be a vital brake on developing nuclear weapons and thereby promote nuclear non-proliferation and disarmament. The preamble to the Non-Proliferation Treaty of 1968 talked boldly of achieving ‘the discontinuance of all test explosions of nuclear weapons for all time’.

But then it took almost thirty more years and hundreds more nuclear test explosions before the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT) was agreed in 1996. This is one of the world’s landmark treaties. What a difference it has made.

Between 1945 and 1996 there were more than two thousand nuclear weapons tests. In the 28 years since 1996, there have been fewer than a dozen. In this century only six tests have been conducted, all by North Korea.

The Treaty relies on a network of over 300 scientific monitoring facilities around the world that can quickly detect a nuclear test notably smaller than the Hiroshima explosion and pinpoint its location. No state anywhere on Earth can conduct a nuclear weapons test in secret.

The CTBT has near universal international support. 187 States have signed it and 178 have ratified it. With ten new ratifications since 2021, there is global momentum against renewed nuclear testing with enthusiasm among smaller states especially high.

Despite these gains, current international uncertainty challenges the global norm against nuclear testing created by the CTBT. What if we see renewed nuclear testing, or even the use of a nuclear weapon in a conflict? We would face a disastrous collapse in international trust and solidarity. A return to the days of unrestrained nuclear testing would leave no state safe, no community safe, no-one on Earth unaffected.

There’s always plenty of talk about learning from mistakes. In this case let’s learn from successes. The CTBT brings together the best of diplomacy with the very latest technology for an unambiguous common global good. It builds transparency and trust, just when transparency and trust look to be in dwindling supply.

On the International Day against Nuclear Tests, the United Nations General Assembly high-level meeting will be convened. On this occasion, we call on all states to be open to the bold but principled decisions needed to reach a final global consensus under the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty. To end nuclear testing once and for all. Enough is enough.

.............................................................

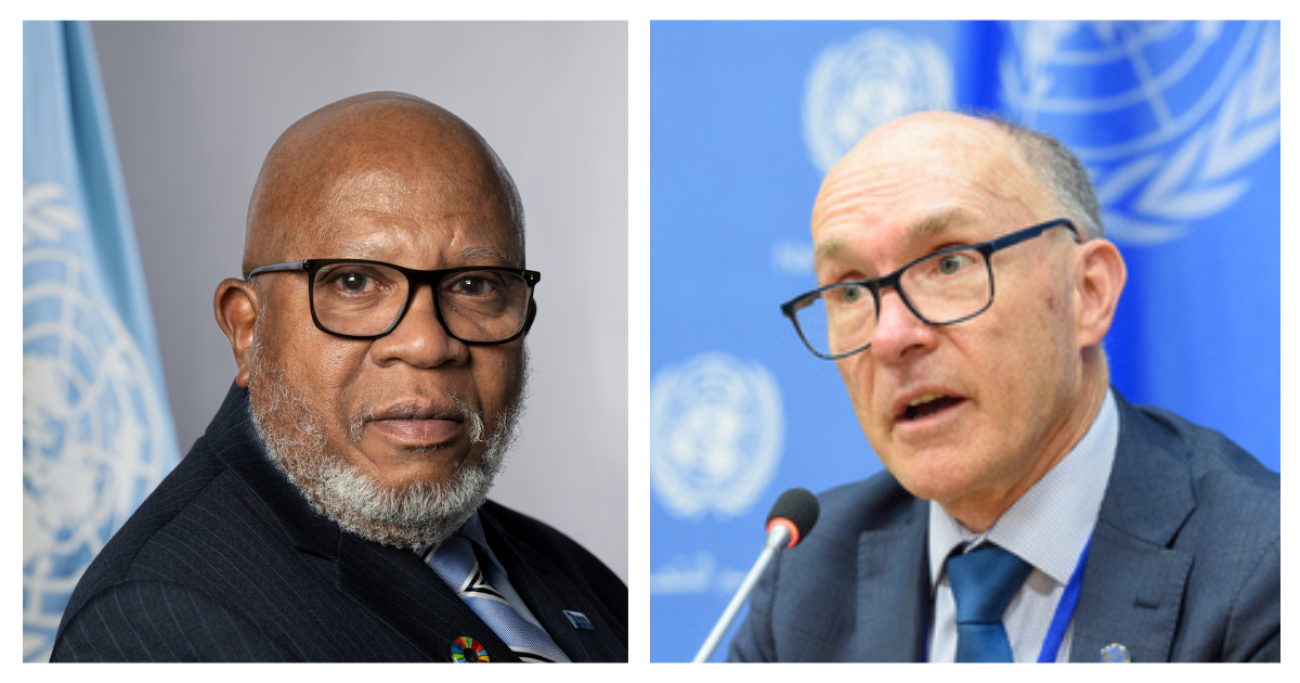

Ambassador Dennis Francis is the President of the UN General Assembly, at its seventy-eighth session

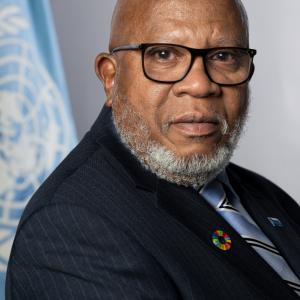

Dr Robert Floyd is the Executive Secretary of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization.